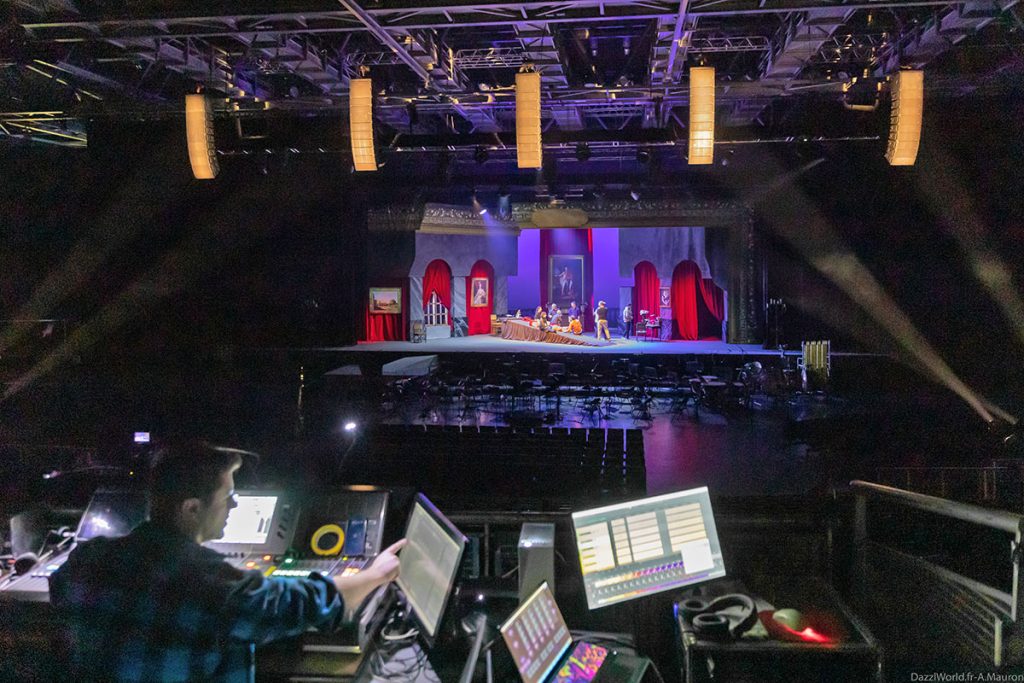

The Fabrique Opéra Val de Loire inaugurated the cooperative opera concept in Orléans in 2013. By programming one opera each year in a venue able to host as many people as possible, the association is making opera more widely accessible and popular. With adapted set designs and staging that includes narration in French, the show provides new keys to greater comprehension, thus reaching out to the broadest possible audience.

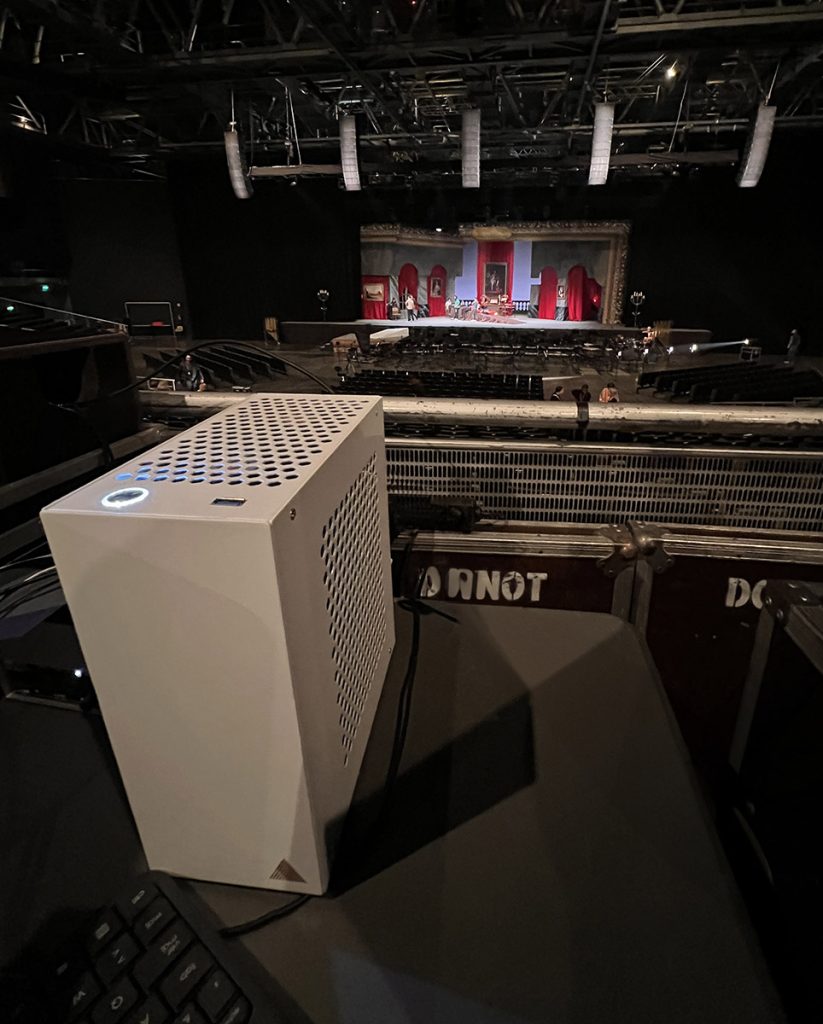

This year we returned to the Fabrique Opéra at the Zénith in Orléans for a performance of La Tosca, this time with an added dimension. Thanks to system engineer Franck Niederoest, and the support of Adamson and their French distributor DV2, the sound reinforcement for the show was spatialized using the FletcherMachine, a first for the production and for the technical team.

The result was a satisfying sonic experience and the awareness of the audience that they were sharing in an extraordinary event. After this, it will be difficult to go back to the way things were before. The best way to understand the benefits of spatialized audio is to listen to Séverine Gallou and Sylvain Béziat, who did the mixing, and Franck Niederoest, who set up the system.

For Franck Niederoest, the project was a first. The sound system was set up after several conversations with Julien Poirot – responsible for System Support and Education at DV2 – about the rules to follow for this type of project, as well as the adaptations required to cope with its constraints. A day of preparation with the Adamson team and DV2 helped define the approach to spatialization and confirm the right system to deploy. It was easy to implement, quickly delivering the desired results..

SLU : Can you tell us about the spatialized audio system installed for this opera?

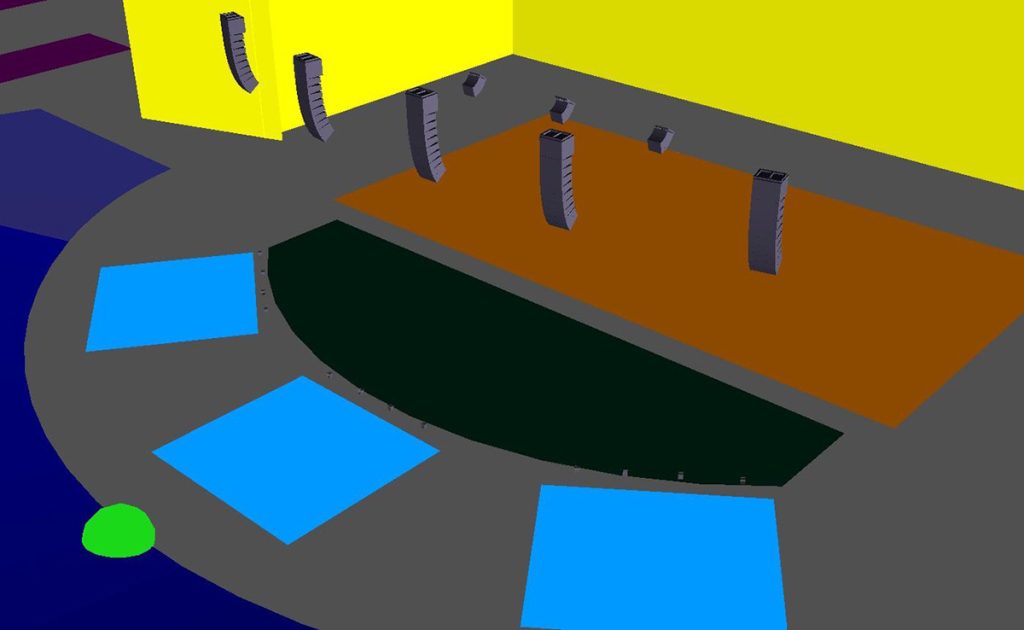

Franck Niederoest : The Adamson system consisted of five main FoH arrays, each composed of nine Adamson S10 enclosures suspended under a single S119 subwoofer. On the floor we had three lines of four IS5Cs in front of each section of the floor seating.

For monitors, there was a row of three hangs of four CS7P amplified enclosures each, flown from the ceiling. This system was fully spatialized by a FletcherMachine (AFM) Traveler 64/32 Dante.

SLU : Spatialized monitoring is a rare thing…

Franck Niederoest : The big advantage of this spatialized monitoring is its efficiency and speed. With this option, the monitors are, apart from a few details, a replica of the front-of-house mix. So as soon as the front-of-house balance was ready, it was immediately ready in the monitors too, and the singers were able to work immediately with a sound that corresponded visually to the orchestra. The mixing engineers then made improvements by choosing in detail which sound objects they would send. We just added a few speakers in areas obstructed by the scenery.

SLU : Where did this idea come from?

Franck Niederoest : During the day that we spent preparing with Adamson and DV2 on the FletcherMachine, we discussed how we could quickly and efficiently generate the audio for the monitors. Julien Poirot came up with the idea of this spatialized line. We just had to add one more layer to the FletcherMachine.

SLU : How many layers did you use altogether?

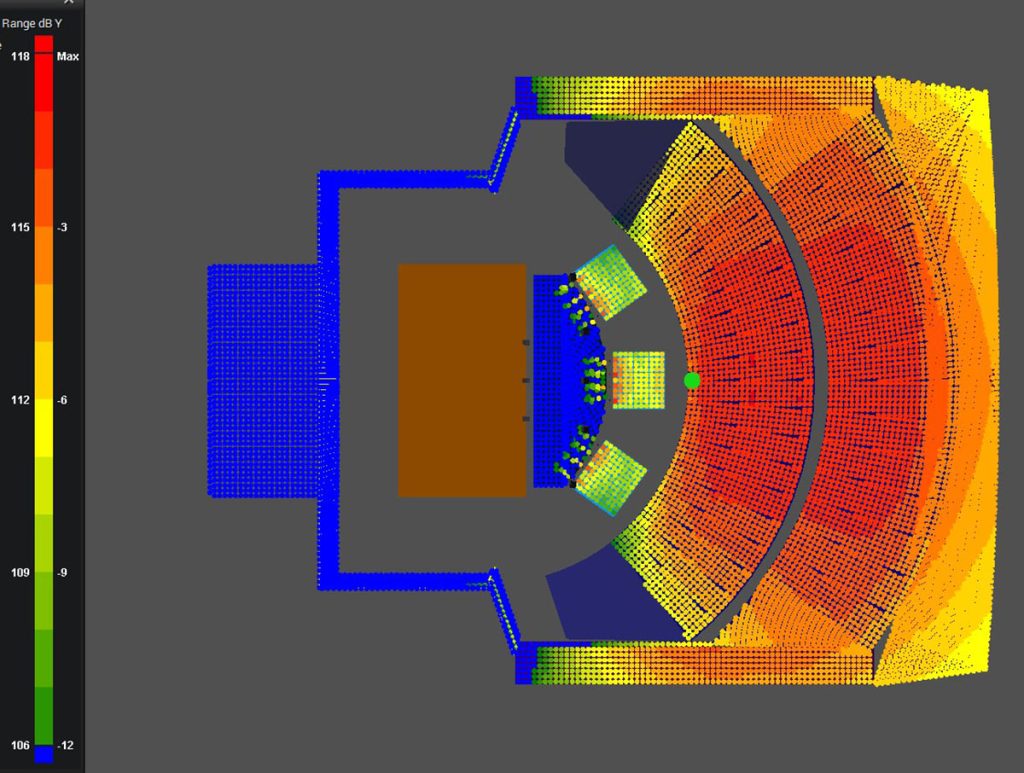

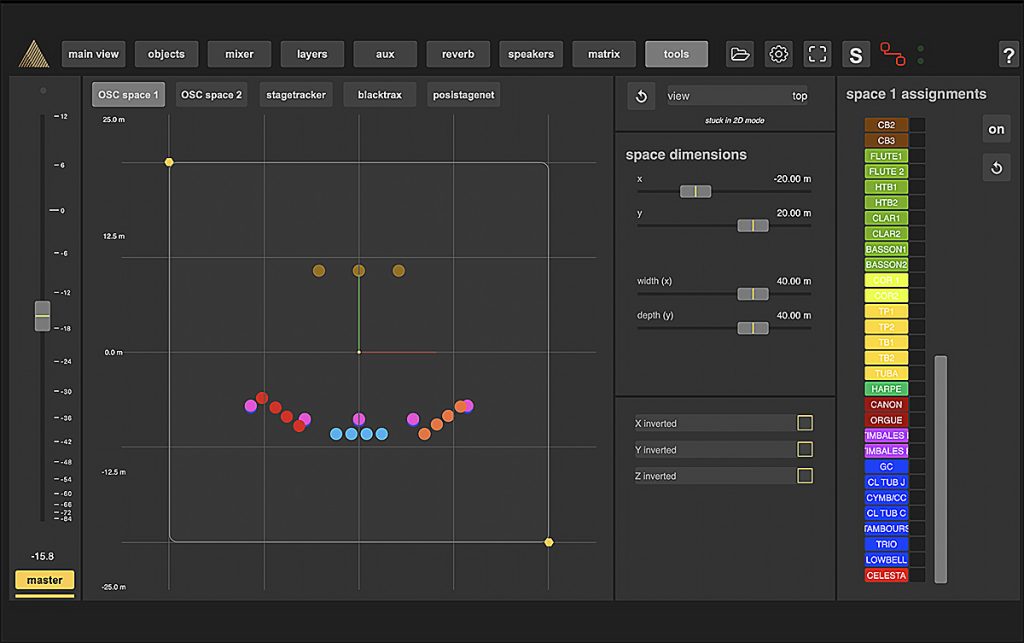

Franck Niederoest : The complete spatialization of the mix was managed with six layers. A main layer for the five FoH arrays, one for the subs – yes, we also work with subs in spatialized mode – three layers for the front fills, so that we can adjust the mix for each section on the floor, and a final layer for the monitors.

SLU : How did you go about setting up the system?

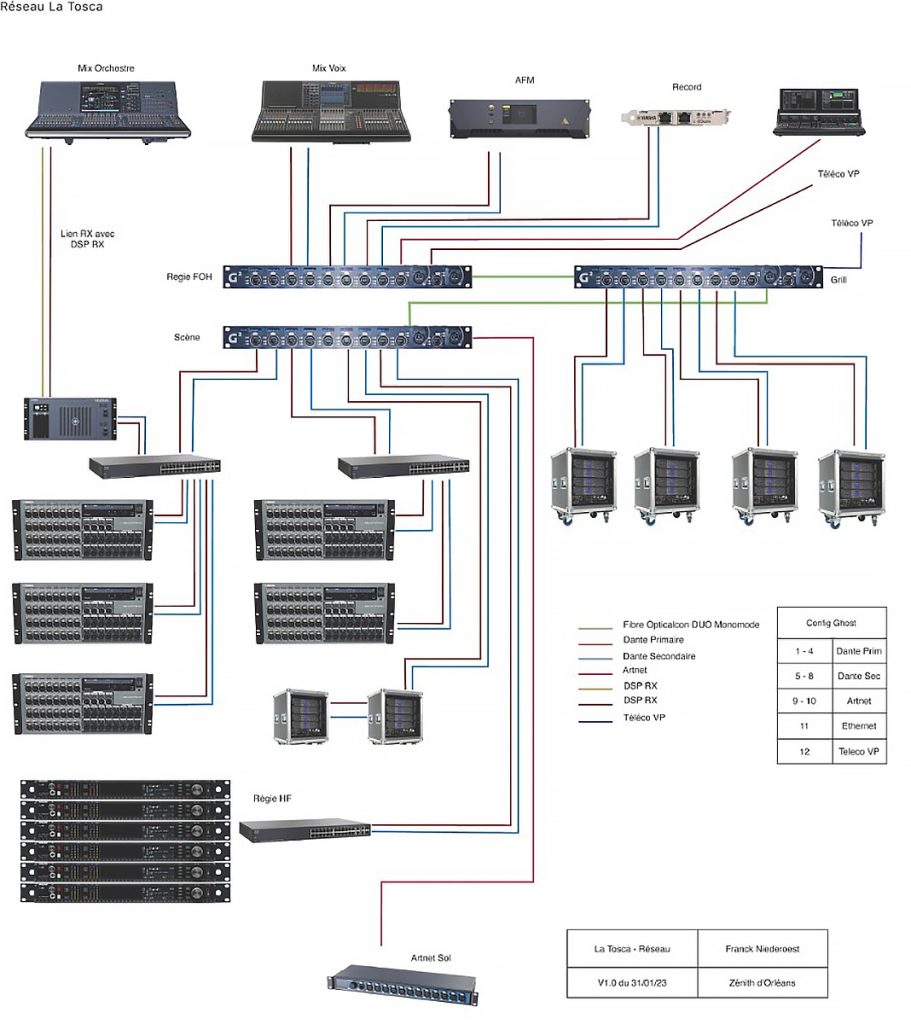

Franck Niederoest : It was the first time I’d set up a spatialized system, but I can’t say it was particularly complicated. It requires a bit more work because there are more rigging points and hoists, more speaker boxes, a few more amps, but it’s nothing dramatic. It’s just a different process. Once it’s all been hung up in the air, we do an initial routing to calibrate it and take our measurements. Once the calibration is complete, we move on to routing through the FletcherMachine. All this is done via Dante and it all goes very smoothly.

I calibrated it one array at a time, so as to obtain the same response on each of them. I do multi-measurements from four points, in the air and on the ground for the average. That’s all I do. The rest is handled by the FletcherMachine.

For the front fills, it was a little different. The difficulty here in an arena was to establish a good transition between the proximity of the orchestra to the front rows and the clusters that covered the stands.

On the floor, we created a mix between the direct sound of the orchestra and the front fills with the IS5Cs, into which the instruments and vocals were simply sent for reinforcement. It was a very good compromise and a bit of a challenge for the sound engineer.

SLU : What about distribution and amplification?

Franck Niederoest : All the signal distribution was managed via Dante in 48 kHz mode, since all the consoles, amplifiers and processors were linked and therefore set to 48 kHz, due to this limit of the CL5, and all this was managed on six layers of the FletcherMachine. Amplification of the complete spatialized sound system was provided by 13 PLM20K44s and 3 PLM10000Qs.

SLU : Was this spatialized system easy to install?

Franck Niederoest : It’s always a challenge to fit the sound package and the lighting package together. With all the constraints of the Zenith and those of integrating the orchestra, it was a good little challenge and a lot of AutoCAD and 3D to figure out how everything was going to work well together. With a traditional system, we would have opened up a bit more and used a central array and front fills, so there weren’t that many differences.

SLU : So, compared with a non-spatialized sound system, what’s your impression?

Franck Niederoest : The huge advantage I felt was that each cabinet had more dynamics and bandwidth, which gave the system much more spaciousness. I thought that just the five subwoofers in the air would be a bit strained… but for symphonic music, it was impeccable. It really made me stop and think.

SLU : So, what about the future?

Franck Niederoest : All in all, this was a fantastic adventure. Now I want to do more. We’re going to do it again next year. The future project will tell us whether we keep the FletcherMachine Traveler 64/32 with its six output layers or whether we’ll have to switch to the FletcherMachine Stage Standard, which has eight layers in a 64/64 format. We had a very nice aperture, with 22.8 meters of stage and 5.8 meters between each array. I might add two smaller ones at the ends.

I’d also like to place a few speakers around in the auditorium, to add an extra dimension. Just a few boxes flown from the ceiling to provide more of an envelope at the back of the grand stands and, for example, help diffuse the reflections a little more. With a large venue like Zenith, I’m not ready to go for a full 360° for reasons of coherence of perception, but the addition of a surround system to give the room a little more body seems like a good compromise to me.

Now that the system has been deployed, we’re back with the sound engineers who worked on the shows: Séverine Gallou for the orchestral mix and Sylvain Béziat for the vocal mix. It was a first for them too, and a hugely satisfying one, as you’ll see.

SLU : To begin with, tell us about yourselves and what your specialities are?

Séverine Gallou : I started working in live sound in 2003 after a stint in industrial acoustics and a period at ISB. My personal tastes drew me towards acoustic music, world music, jazz and classical, covering both front of house and monitor positions.

I met the team at “Violon sur le sable”, who organize concerts with a symphony orchestra on the beach at Royan on the Atlantic coast, where I do the monitors. They gave me my first taste of classical music sound systems back in 2005.

If you’ve never heard of Un Violon sur le Sable, click here for our report on this festival, which is both unique and very sandy for the equipment: Un violon, des potes et du STM dans le sable de Royan (A violin, some friends and STM in the sand at Royan).

Sylvain Béziat : I do a lot of live music. I grew up on jazz and world music, with a strong connection to acoustics. I joined the Fabrique Opéra in its first year in Orléans and we’ve been together ever since. This is my ninth year, and the first time I’ve used a spatialized system. So it was a big unknown on an important project with established habits, which we all know are as valuable as they are dangerous in this business. You have to challenge yourself. I’ve been wanting to try it for a long time, because it’s totally suited to the style of music I do.

SLU : On this opera, you are two engineers working together.

Séverine Gallou : Yes, the principle of the Fabrique Opéra is to have two mixing boards. One for mixing the voices, managed by Sylvain Béziat, and one for mixing the orchestra, which I do. There is no monitor console.

SLU : What was the mixing setup like?

Séverine Gallou : We mixed on Yamaha. I used a Rivage PM3 for the orchestra and Sylvain used a CL5 for the voices. I had two Rio D2 stage racks for the orchestra, for a total of 64 channels. We didn’t use any on-board miking, so it was all still overheads, but with the emphasis on proximity.

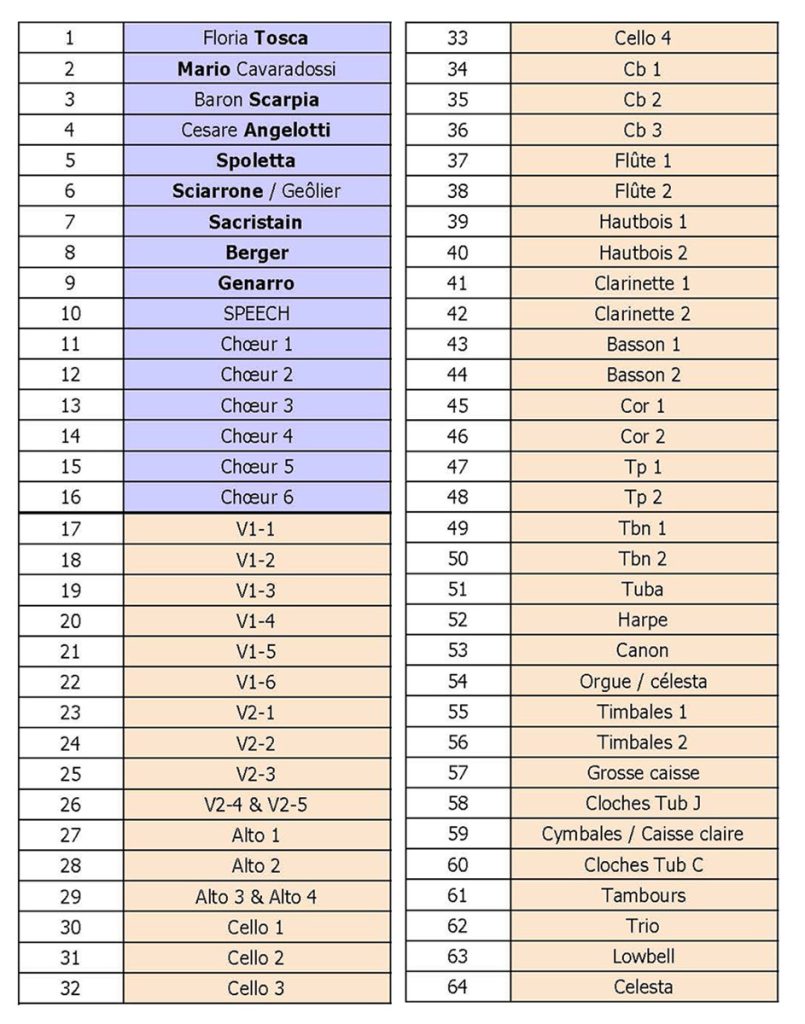

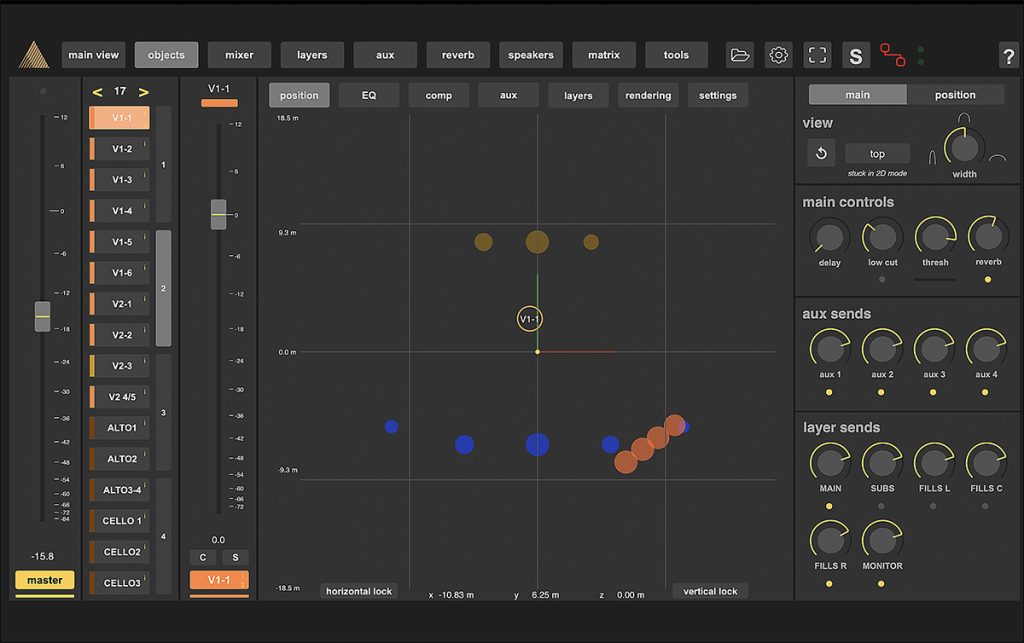

I had about fifty sources, which I sent individually in direct out to the FletcherMachine. I just made a few groupings to fit within the maximum of 64 objects allowed by our configuration. I also left some spare objects, so that I could cover any unforeseen needs during the rehearsals.

SLU : So there were actually two of you using the FletcherMachine?

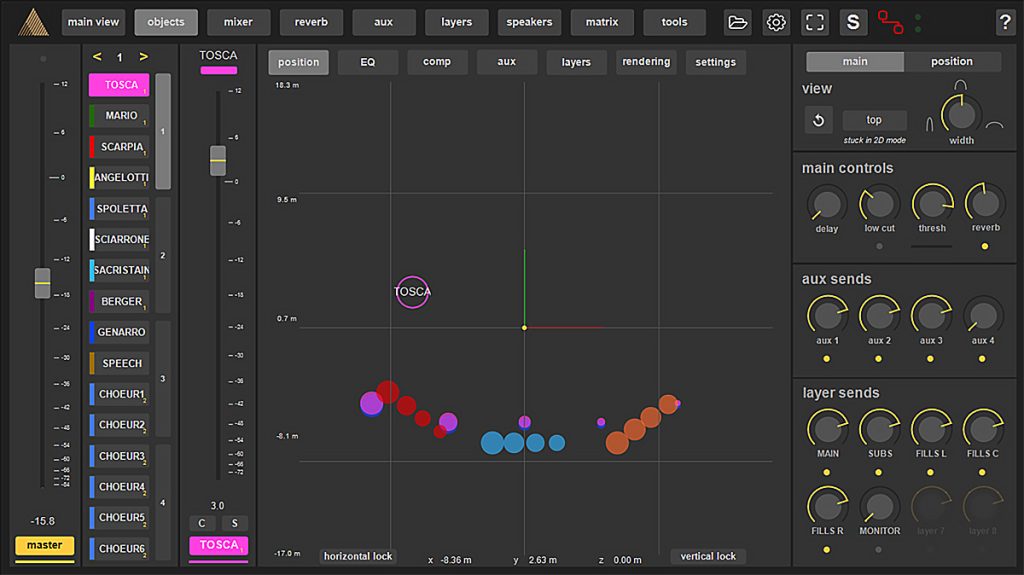

Séverine Gallou : Yes. I’d send my direct outputs to the Fletcher and Sylvain would also send his for the voices. It was the Fletcher that mixed everything. We each had a remote computer with a touch screen to work on the same FletcherMachine. I also had a tablet that I could use to adjust the spatialization as I moved around the room. I used it for the front-fill mixes for the floor seating.

SLU : What changes did you have to make to your usual setup?

Sylvain Béziat : We usually use a left/right configuration, where the stage front is very wide, so we compensate with a central array. In terms of consoles, we had one that managed the voices and monitors, and another that went out front and took the voice premixes and mixed them with the whole orchestra.

Here, with the FletcherMachine, none of that could work. So we had to forget everything and use object mixing. Before the day of preparation, it seemed complex and just imagining it all took on enormous dimensions. In fact, I discovered that spatialization simplified things and made a lot of sense. It all came about with amazing simplicity and naturalness, and I have to say, it was delightful. I really enjoyed working on the project over those ten days.

SLU : Was the preparation day that you mentioned essential?

Sylvain Béziat : The prep day was extremely important. We had to rethink everything. You don’t arrive with your stereo mix to listen to… you need a multitrack. It allowed us to prepare everything and that was indispensable.

Séverine Gallou : Yes, of course, in order to get to know the FletcherMachine, which we weren’t familiar with. What’s more, you can get a free 24-input, 12-output virtual machine that runs on your own computer. I used it to train on the software before coming to Orléans.

I was able to put five small speakers in my living room with a simple sound card, plus a virtual soundcheck using an internal Blackhole virtual sound card that played orchestral instruments. I was able to get to know the software and do some very interesting audio tests.

SLU : Was it risky to opt to use a spatialized layer for the monitors?

Sylvain Béziat : When the idea of spatialized monitors was suggested to me, it seemed complicated in my mind. In the beginning I mixed the monitors, but with the Fletcher that wasn’t possible anymore. Generally I get a premix from the orchestra which I mix with the vocal monitors, and with an iPad I go on stage to adjust it. By using this spatialized line of speakers, the monitors spread out like the FoH system, no matter where you were, the perception of the sound image of the orchestra was perfect.

We ended up with a very natural sound and very uniform coverage of the stage. The result was surprising compared to very directional side-fill monitors. I had the impression that the orchestra was huge but I couldn’t hear the speakers. The singers didn’t have the proximity defect of conventional monitor speakers and it was very comfortable for them as they moved around. I just kept some proximity speakers around for additional reinforcement.

Séverine Gallou : This is a good example of what we mean when we talk about spatialization. Opera singers especially need monitoring from the orchestra and not necessarily themselves, because they have powerful voices. I usually do mono orchestral mixes in side-fills. But while switching from a stereo mix to mono remains coherent, with a spatialized mix as a starting point, I wondered how I was going to do it.

What’s more, as we’ll see, the processing I have to do for an immersive mix is quite different from that needed for a stereo mix, and even more so than for a mono mix. So I was very worried about that. The idea of spatializing the monitors came from this assessment and it proved to be extremely effective. We used a layer for the monitors that naturally followed the object mix, mirroring the front-of-house mix.

SLU : What about the singers?

Séverine Gallou : The singers appreciated this system, which was consistent with the physical position of the orchestra. Unlike with side-fill monitoring, there was no masking effect from the extras on stage. This was a significant added value for them. Usually, monitoring for singers is complicated. Louder…softer… a constant issue during rehearsals.

After the first day of setting up, it was ready to go. All the singers forgot that there were monitors. I just positioned the monitor speakers within the space in the FletcherMachine. All the mixing calculations in these three speaker arrays were actually done by the Fletcher. I hardly touched anything and everything was spot on. We had just two or three speakers to cover areas obscured by the scenery, into which I sent a simple mono downmix from the Fletcher, as well as other speakers for the dressing rooms and backstage.

SLU : Is this your first object mix?

Séverine Gallou : It was the first time I’d mixed spatialized objects. We were introduced to the FletcherMachine during our day of preparation. It was really helpful because, at first, I thought I was going to manage groups of instruments in the objects, for example 1st violins, 2nd violins…

But when I compared the spatialization of a stereo group of instruments with that of one object per instrument, I realized that it was like night and day.

With a stereo group, you have to do some fancy summing and send it to the spatialization, which is no longer the case with an object for each microphone. So I reconsidered all my preconceived ideas and sent all my microphone sources as direct outputs to dedicated objects.

SLU : Did you get the hang of it quickly?

Séverine Gallou : Pretty much. The key issue was how I placed my objects to begin with. I placed them visually, in their actual position in the orchestra, and then I refined them by listening. I’m firmly convinced that the crux of the matter is to have a system that’s set up properly so that, once the object is in the machine, if it’s placed in the right place, it reproduces the sound very naturally. Especially because here we have the direct source of the orchestra combined with it.

Sylvain Béziat : I’d chosen a CL5 because I was a bit worried about running a system I didn’t know very well. With this console that I know by heart, I was at ease. I wanted to be sure of this aspect so that I could concentrate fully on getting to know the immersive aspects.

Now I have to admit that, for next year, I’d like to switch to a console that allows me to have direct control over the objects. While the remote screen is essential for controlling positions and movements in real time, I got used to it very quickly.

I thought it was great to be able to visualize the levels of an object in the different speakers. It’s a very important point that reassures you and shows exactly what’s happening in the sound system. You understand very quickly and you can avoid unpleasant surprises when you move an object.

SLU : What were the rehearsals like?

Séverine Gallou : We had several rehearsals for the artistic and staging aspects. When they start, we must be ready with the sound equipment. When the orchestra arrives, it starts directly with the singers. So I’m already supposed to be able to provide orchestral sound on stage. I was able to negotiate half an hour of orchestra alone before the singers arrived and that was enough. The objects were ready, we’d programmed them in advance, and I was able to deliver sound even faster than with a traditional left/right.

SLU : How did you manage the different zones of the audience?

Séverine Gallou : With the FletcherMachine layers. We had the front layer for the arrays at the front, the sub layer positioned in the same place, and then three layers of four small speakers, one layer for each floor-seating area to give them individual spatialization.

As these speakers are in the FletcherMachine at their physical position, there is not at all the same thing in each of these layers. But I could choose which layer to send each object to. I went and listened to each front fill with nothing in the main arrays and just added the instrument objects that were missing. It was a very transparent method.

For example, for the stage-left seating area, I would add more harps and violins. In the stage-right area, a little more woodwinds or bassoons. I really did it “à la carte” for each seating area. In the center there’s practically nothing because the orchestra is naturally acoustically balanced. Of course Sylvain sent all the singers’ voices there to bring back presence and intelligibility.

SLU : Despite the proximity of the audience, did it work?

Séverine Gallou : I only did it this way because the audience sits still and doesn’t move. We kept 1.5 meters between the front fills and the first row. The audience is therefore in the configuration required by this principle of spatialization, that is, in the coverage of at least three loudspeakers.

SLU : What about the main front-of-house layer?

Séverine Gallou : The main system only covered the stands, which was a good thing. If we’d chosen to go all the way to the floor with the arrays placed so high up, it would have given the impression that the sound was coming from the ceiling.

SLU : The subwoofers are spatialized with the FletcherMachine?

Séverine Gallou : The spectrum does go down with the double basses, timpani, etc… What I don’t like to do with classical music is to use subs on the floor, because you get an unwanted ground effect. Here, since I had a separate layer, I could choose the objects I sent to the subs.

I really liked the fact that there was no central point. As the subwoofer was integrated into the sound source, the bass of each of the instruments came out well at their position in the spatialization. You could say that the subs were spatialized in this way. For classical music, this is very nice and very natural. The fact that the arrays covered the whole spectrum with spatial coherence was a real plus.

SLU : And did you have to supply stem feeds?

Séverine Gallou : We still need feeds for video recording. I was able to choose what I put in it. So I supplied the orchestra in stereo and two stems, one for the lead voices and one for the choirs. I was amazed by the quality of the Fletcher’s mono and stereo downmixes.

SLU : How did you handle the positioning of the objects for the orchestra?

Séverine Gallou : I soon realized that I’d thought too far ahead in terms of the positioning of the objects. In the end, my harp was completely in the stage-right array, but when it came out of the speakers it didn’t give the impression that it was physically coming from where it was.

I had to rethink the scale and proportions to tighten up the spatial image of the orchestra a little. To give myself limits, I went to the extremities and listened to the instruments with my eyes closed. I pointed to where I heard them and when I opened my eyes again if it wasn’t right, I corrected it in the Fletcher so that it still sounded as if the instruments were coming from where they were. That way you’d forget that you had a sound system.

Sylvain Béziat : The voices were going into all the layers. In the monitor layer, however, it wasn’t the case.

SLU : What about objects that moved?

Séverine Gallou : For me, there was no reason to make movements on a static orchestra, but for the voices it made sense, right Sylvain?

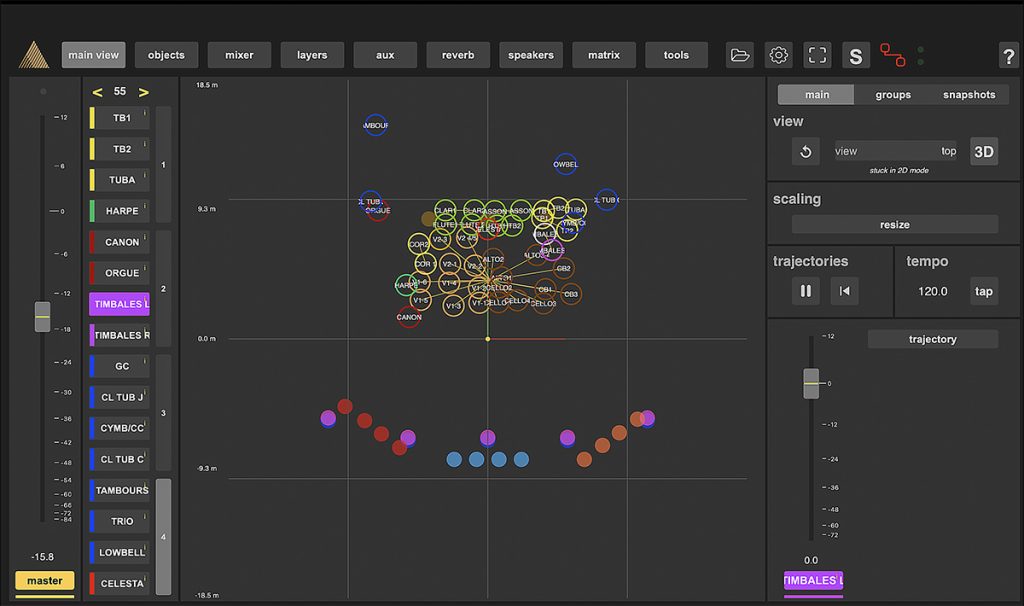

Sylvain Béziat : Of course! At the first rehearsal, I kept the voices in the center, as in stereo, and opened up the choirs a bit. But very quickly I decided that I was going to play around with it a lot more. I had to follow the voices. With La Tosca it’s quite easy. I was able to control it manually, without the help of trackers. I found a way of moving the objects that made the movement very natural.

Many people in the audience noticed that the sound image followed the singer. They appreciated this connection with the visuals, unlike a voice that remains in the center. You have to know the music and follow the staging. As I could only move one object on the screen, I favored certain movements over others and as this attracted the audience’s ear and attention, it worked very well.

I was sending MIDI commands from the CL5 to the Fletcher to recall snapshots. I did this a lot less than usual. I just used it on specific passages to bring a sound object back in. As I was moving the objects in real time, I avoided positional discrepancies between snapshot recalls and the current position. The aim is to keep a firm grip on the Fletcher. But, since we were both working on the same machine, discipline and communication were essential.

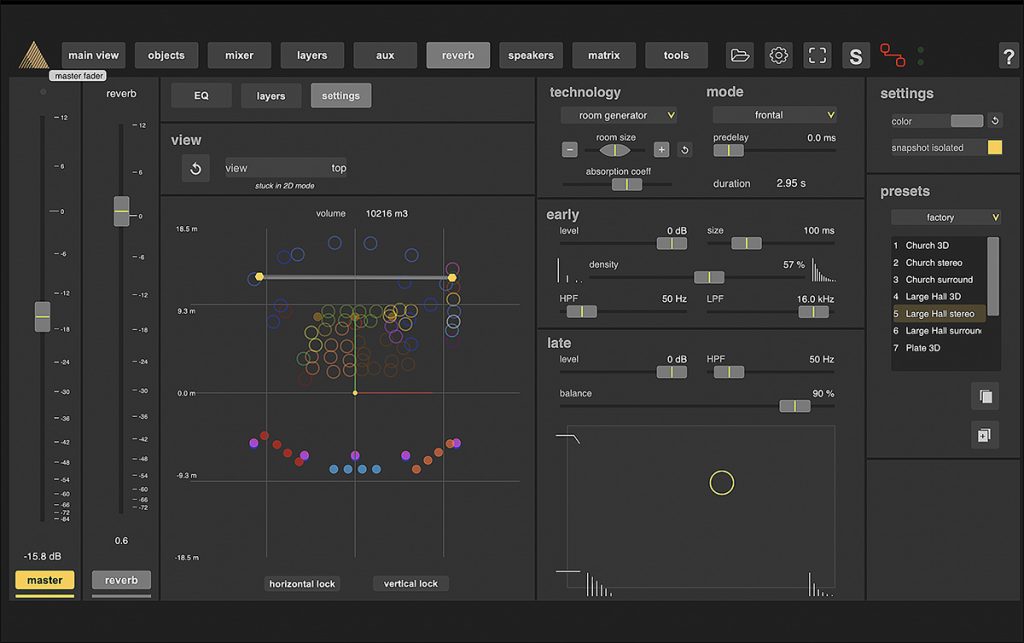

SLU : Did you use any reverb processors?

Séverine Gallou : The only reverb we used was the one included in the FletcherMachine. It works very well, it’s very easy to configure and it’s very natural. With an orchestra, I usually only use one reverb and here I could adjust it for each object as I wished.

I could add a little more on certain instruments like the harp and depending on the proximity of the microphone. For opera, we stick to a hall algorithm, which is natural. What’s more, the Fletcher has a grey bar that lets you see its reflection wall. You can easily adapt the reverb by moving this virtual wall.

Sylvain Béziat : I normally use a Bricasti. But here, I thought it would be absurd to include a stereo reverb in the spatialization. So I also used the Fletcher reverb on the vocals. I thought it sounded really good. No frustrations. It became very simple: you insert the reverb, extend it a little and that’s it. The kit is natural and you find yourself in a Zenith that’s much prettier. Of course, as soon as the audience arrives, we run out of reverb. You readjust and it’s done.

SLU : Which features of the FletcherMachine did you really appreciate?

Sylvain Béziat : I have nothing negative to say about this software. There’s nothing missing. And we were lucky… Sylvain Thévenard, one of the Fletcher developers, came to our rehearsal day. I wanted to make a few small changes and he was able to develop a few things for us on the spot. We were really well supported. The interface makes it easy to see what’s important. It’s a real winner in terms of the user interface.

Séverine Gallou : I found the software very intuitive and straightforward. Working with objects is very well conceived. The fact that you can group objects together is very practical for violins, for example. You can move groups of objects and elements within the group very easily.

There’s also the option to choose the operating mode by object or by layer, with the device managing a delay, a minimum delay or no delay. To be very clear, we’ve only used the minimum delay. But I think that at some point it may be necessary to be able to choose… maybe for the voices?

Sylvain Béziat : We stayed within the minimum delay but I cheated a bit. I used the software visualization to manage the depth of the sources. If I kept the position of the singers in relation to the plane of the loudspeakers, I found that my movements were more awkward. By moving them away from the speaker plane, the lateral movements were more fluid. This increases their reproduction through all the speakers and avoids distortion.

It is also important to select the objects to be moved without modulation, to avoid any type of interference. These operas often feature a narrator. Each time he spoke, I called up a snapshot that placed him closer to my speaker plane, which meant that his voice was really in front of that of the singers, making it even more present for the audience. The singers were mixed into the music whilst the narrator was in front of it.

SLU : In terms of delays, didn’t you handle everything with the spatialization?

Séverine Gallou : Not completely. I had off-stage toms and the conductor told me not to put them in the front-of-house system. But with a full Zenith that doesn’t work. Especially for the audience at the back of the stands! I put a microphone on it and I made an object that was very far away. That’s why I didn’t use the object’s full delay, but put delays in my console.

I also delayed the whole orchestra by measuring with a rangefinder in relation to the zero point on the conductor’s and the first violins. I could have done it in the Fletcher, but in the console I could do an on/off to check if it made a difference. It’s not so easy to tell if it’s going to be good with the different interactions between the microphones. Even here, with the spatialization, it worked really well. With the last row like the clarinets at 6 meters, we were able to restore the precision and clarity of the orchestra.

SLU : So, you tweaked the spatialization system to suit what you wanted to hear?

Séverine Gallou : In reality, we already have latency in our signals from console, to processing, to converters. I created a true zero point on my first row, with the speakers just above it. In the Fletcher, I should have put my first sound objects on this same line. Except that this would have meant that an instrument at far stage-right would have been heard almost exclusively through the stage-right array, and that bothered me.

To open up my spatialization, I virtually moved the objects back in relation to the speakers. You lose a bit of precision in terms of localization but you gain in terms of spatial effect for the listeners at the sides, who are not covered by all of the five arrays.

SLU : Has spatialization changed the way you mix?

Séverine Gallou : I realized very quickly – and this was great – that I was no longer processing as a compromise, but for aesthetic reasons. I was able to open everything up with just low cuts and most of the sound objects weren’t masking each other. You can really feel the difference between the electronic summing in a stereo bus and the acoustic summing that results from spatialization. I did a lot less EQ and in dynamics, where I just use compressors on problematic instruments, I didn’t need anything at all.

I did some equalization to cut out the frequencies that were a bit sensitive or to attenuate bleed between instrument mics, like on the cellos where I cut the treble a bit to attenuate bleed-in from the percussion behind them. At one point, we had a quartet of cellos playing on their own. I released the shelving just for that moment and it was perfect. With spatialization, we don’t have any summing problems, so there’s a lot less processing. It’s much more natural, with less loss and impressive reproduction.

Sylvain Béziat : I let the voices come alive naturally. The sound is so beautiful and natural that I just put a compressor on one voice so as not to have any surprises on an input. You get an impression of power that you don’t get with stereo. In my console, I set things up as usual, with my EQs and my multiband compressors, only to realize that I no longer had any use for them. Just classic high-pass, to avoid unnecessary frequencies.

The voices were much more lively and powerful. I didn’t feel the need to control their dynamics. I let the singers naturally settle into it. If during the rehearsals, when the singers started, it was a bit disturbing as usual, there was no need to panic… When they came back into the dynamic of the orchestra, I didn’t have to do anything else and I could concentrate fully on the objects of the Fletcher and follow them on the stage.

SLU : Are the timbres of the instruments preserved better?

Séverine Gallou : Compared to stereo, it’s obvious. I felt immediately that the timbres needed no correction. We’re not fighting against any disturbing effects in the summing or any other masking effects.

Sylvain Béziat : The timbres of the voices were perfectly reproduced. I use DPA 4060 or 4061, depending on the singer. I usually correct a little. Here, there was no need to, just go on to the next one. I was more impressed with the choir mics, where there was no breathing, the feedback from the monitors was impressively reduced… you really had to go looking for it.

What surprised me even more was my row of KM184s that I put on the floor at the lip of the stage. Here, when I opened them to pick up all the choirs and a soloist, it worked better than usual. I could make the soloist stand out by pushing up his close mic, but much less than usual. The mix with the other suspended choir mics, DPA 4011s, was also surprisingly natural.

SLU : And what about the overall dynamics, which are important in an opera?

Séverine Gallou : We balance the orchestra just once. Whatever the dynamics of their playing, there’s no need to correct the instruments. The amplified sound follows the dynamics of the orchestra. If it’s balanced in terms of composition and direction, we find ourselves in the simple situation of amplifying what’s going on, in total transparency. That’s exactly what we’re looking for in classical music.

Sylvain Béziat : Everything is perfectly respected. You really forget about the system. Above all, your ears don’t lean towards the speakers. The image is correctly conveyed, including during pianissimo passages. This can be disconcerting, but in real acoustics, you must go looking for an opera that plays pianissimo. Here it’s the same.

In the fortissimo passages, the orchestra becomes enormous, but without any aggressiveness from the speakers. It worked very well, even in the front fills, where the mix wasn’t as complete as in the main arrays to blend in with the direct acoustic sound of the orchestra, which also worked very well. So there was absolutely nothing to do… It was overwhelming!

SLU : So, the job of mixing is easier?

Séverine Gallou : Yes. As I’m really trying to be faithful to the orchestra, in the end it simplifies my job. It’s much easier to get a balanced orchestra. I was really impressed by the dynamics. I had between 10 and 12 dB of headroom on my master fader before the first slight problem, which never happens in classical music with all the mics open. Even though I already had some headroom because of the configuration of the speakers in front of the orchestra and facing the stands, I clearly felt that it wasn’t just that. It’s also the fact that the summing is different.

Sylvain Béziat : The first day is often unpleasant because you don’t have time to balance everything, and the singers are often unhappy. It’s a complicated thing to do on a human level. Here, with spatialization, not at all. I got great voices immediately. The dynamics didn’t overwhelm them. This is a good illustration of how things work naturally without any great effort. You could probably go further with spatialization, but straight away it worked very well.

SLU : Did you have more freedom?

Séverine Gallou : Yes, I took the liberty of adding a bit more to the dynamics to put a bit more emphasis on the dramatization of the end of scenes or at the end of acts. Then I could push the master (for me, the master is basically a DCA in which I have everything). I make DCAs for individual sections, and of course all my direct outputs are post-processing and post-fader. I want to support the moment even more to get a more cinematic orchestral sound.

We also play in arenas such as the Zenith, and we’re in front of audiences from all walks of life, so we have performances that are a bit out of the ordinary, right down to the staging, which allows us to accompany them. When we were in stereo, I used to pick up the voices in the console and balance them with the orchestra. That’s no longer possible here because everything goes into the objects on the Fletcher. With this DCA I can correct the balance if necessary.

Sylvain Béziat : I didn’t actually need to keep my hand on the fader anymore. It felt a lot more like making music than doing sound. It’s a new way of approaching a mix. It reminds me of the early days of digital consoles. Re-learning how to do things. But this is a really big step forward.

SLU : Does spatialization improve the sound of certain instruments?

Séverine Gallou : In fact, all the instruments in the lower registers have a better presence. I didn’t have to cut the bottom end as much to avoid rumble, so I lost less of their fullness. The timbre is better maintained and that makes life easier. The double basses, cellos and bassoons are better separated in this part of the spectrum, which is complicated to manage in stereo. There’s no electronic summing and phase problems are avoided, resulting in prettier timbres in the lower registers.

Sylvain Béziat : The voices come through naturally. The same goes for the choirs, for which I used to use a bunch of KM184s at the lip of the stage. Well, with the FletcherMachine, I had the impression of having just one more microphone. No phase problems. As we only had 64 possible objects in all, I had to make groups for the choruses with a maximum of six objects. I also adhered to the visual placement for them. It would be great to have one object per microphone.

SLU : Could you then choose other microphones, change your habits?

Séverine Gallou : Yes, especially in terms of directivity. I tend to use hypercardioid so as not to have too much mess on the cellos, for example, but it’s more of a medium range. When I’m spatializing, I’m more inclined to switch to cardioid which will give me more warmth at the bottom because I know that the summing with its neighbors won’t be destructive. And putting in more large diaphragms would also be less of a penalty than with stereo. It gives you ideas when you have more leeway.

Sylvain Béziat : When we choose a microphone, it’s to achieve a certain result and often to overcome sound capture problems. Here, there are so few phase problems or sound pick-up compromises to resolve that we are led to rethink our usual practices and use better microphones in certain cases.

SLU : Is it easier to work with the artistic director?

Séverine Gallou : The conductor realizes that there are fewer feedback problems when we do the rehearsals. And above all, since we had a virtual soundcheck, we were able to have him listen to the performance. He was blown away, with tears in his eyes. He moved from one side of the arena to the other, all over the stands. We couldn’t demonstrate the front fills because the orchestra wasn’t playing live to blend with it. He was amazed, very moved and the first to say “there’s no going back”.

Sylvain Béziat : On the first day of rehearsals, we’d never had a result like this without a soundcheck. When we raised the faders, we immediately had something we could use, in the front and the monitors. From then on we spent more time making music than sorting out sound problems. I didn’t feel like I was making any compromises.

With a commonsense approach, it works. When Clément Joubert, the conductor and driving force behind the project, comes up to you and says it’s brilliant, you simply reply that you’re just reproducing what he does.

SLU : What about the audience? Did they notice the difference?

Séverine Gallou : I think a lot of the audience must have had the impression that there was no amplified sound. A few people came to congratulate us, which is generally very rare. On the other hand, we didn’t get any negative comments, which is even more uncommon.

A lot of the people who came up to us were musicians, telling us that they’d never heard anything like it. Of course, the same was true of the musicians in the orchestra during the virtual soundcheck. All good feedback, it never happens like this. It’s the first time I’ve achieved the goal of forgetting that the concert has sound reinforcement, and it’s really thanks to this spatialization system.

Sylvain Béziat : Deep down, I’ve never been so proud of myself as I was after that performance. It’s a real thrill. The satisfaction doesn’t really come from the job I did, but from this system, which is amazing and allows us to be with the artists, without having to make any technical compromises.

SLU : Well, before we finish this interesting conversation, would you like to add anything else in conclusion?

Séverine Gallou : I had so much fun and I had such a blast at this show that it was worth talking about. I’d have a lot to say, and I think the FletcherMachine deserves it. In terms of the results, as well as in terms of its use, the tool is undeniably attractive and effective.

Sylvain Béziat : Spatialization allows us to make even the most reluctant orchestra conductor accept a sound system. The music is really amplified, it’s bigger at every level. Stereo used to make the music sound bigger, but also coarser. Not this time! It’s just overwhelming. When you come back the next day to a traditional system, you’ve got a bit of a hangover. For me, this concert is the concert of the year, and I experienced an unprecedented pleasure in mixing.

The cherry on the cake. I promise, just one!

After this long article, and I thank you for having read it to the end, I don’t think it’s necessary to add anything to the argument in favor of a spatialized sound system for an acoustic orchestra performance. It’s the engineers who talk about it best… and when they’re so happy to be doing their job, interviewing them is as much a pleasure as listening to the sound of their mix. We look forward to seeing you at the next performance of the Fabrique Opéra, with spatialized sound, of course.

For more information, visit:

– AFM Adamson FletcherMachine

– The DV2 website

– La Fabrique Opéra website