The celebrations marking Sennheiser’s 80th anniversary concluded with visits to the company’s headquarters in Wedemark, Germany, and to Neumann’s Berlin facility home of one of the most respected manufacturers of large-diaphragm condenser microphones. Two days spent among passionate professionals, driven at full pace, and clearly designed as engineers talking to engineers.

Visiting a corporate site that combines R&D, manufacturing, and final assembly for brands of this stature is always a challenge both for the journalists invited and for the host company, which goes to great lengths to deliver a flawless experience while keeping sensitive areas under tight control.

In practice, what we are allowed to see is necessarily curated. From a distance, we catch glimpses; we sense atmospheres; we infer far more than we’re shown. In today’s fiercely competitive global pro-audio market, factory visits are tightly managed—even when they’re genuinely fascinating. So what can really be taken away?

Strong impressions, sometimes even firm convictions, about the engineering discipline, production capability, and product quality on display. But above all, the recurring realization that the core strength of any company lies in the people who animate it, and in the passion that drives them whether in Wedemark at Sennheiser or in Berlin at Neumann.

The Sennheiser team whom we thank again for their openness, professionalism, and availability—guided us through the group’s headquarters, showing the various buildings that trace the company’s evolution. What began as a single farmhouse in a green field (still standing today) has expanded into a campus whose buildings have changed purpose over time while retaining their original architectural character.

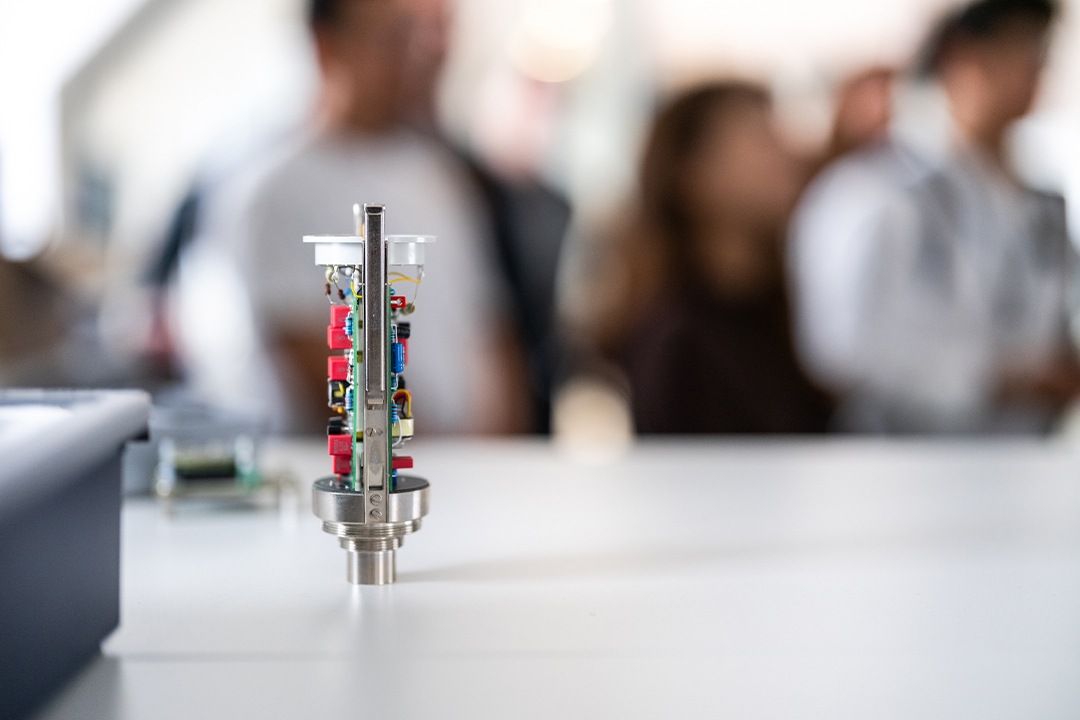

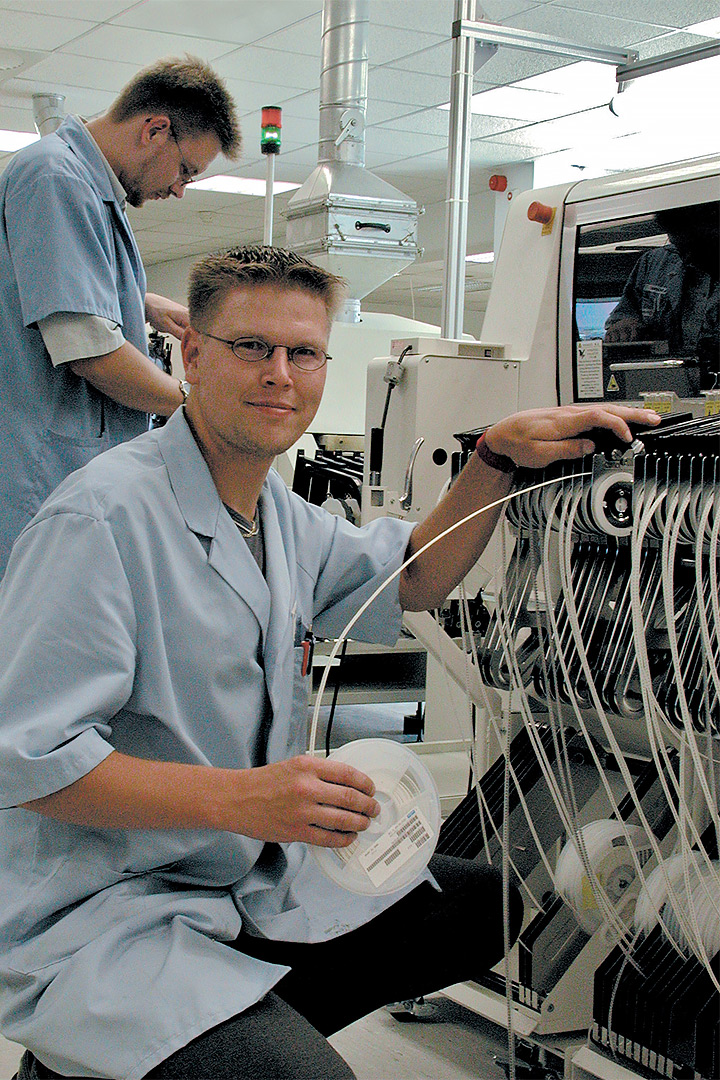

Some now house R&D (strictly off-limits), others final assembly lines, while the newest facilities are dedicated to SMT production: reels of micro-components, high-speed pick-and-place machines, wave soldering, and reflow ovens. Production tempos are high, driven by the success of several recent product lines.

Automation is omnipresent, but it hasn’t eliminated the need for human expertise. Highly specialized operators working under binocular microscopes with astonishing manual precision still perform tasks that machines cannot yet execute with a sufficiently low rejection rate, or within a cycle time that makes automation worthwhile.

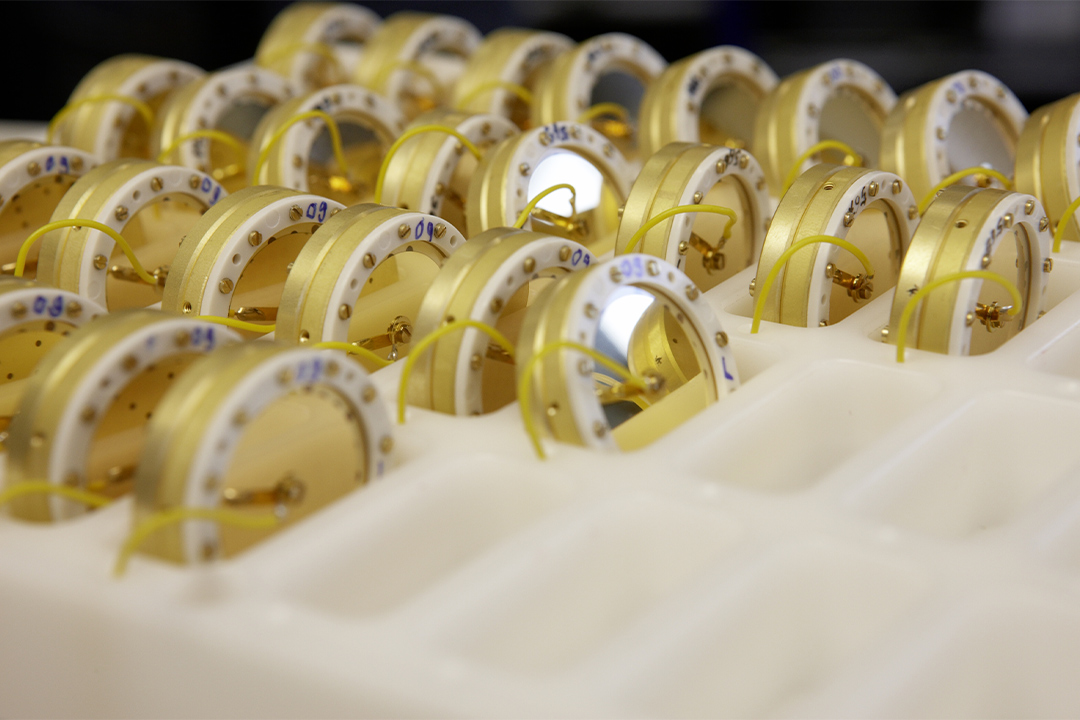

The most compelling illustration of this human factor is found in what insiders call the Neumann “square” a room within a room. Here, ultra-specialized technicians work in air with rigorously controlled temperature and humidity, stretching diaphragms and assembling condenser capsules for microphones that have shaped the history of recorded sound.

The gestures involved have been passed down for more than half a century. While the process may appear simple to the uninitiated, no machine has yet proven capable of matching human hands for speed, precision, and consistency at this level.

Quality control is omnipresent. Every transducer, sensor, circuit board, and finished product passes through dedicated test fixtures and computer-controlled measurement systems, ensuring full functionality and interchangeability.

Microphones go even further. Tolerances are tightened to extreme levels for matched pairs. Software compares frequency responses across batches of 100 microphones or more, sometimes identifying only one or at most two pairs with less than 0.3 dB deviation between capsules.

Even the finest hardware would be meaningless without people capable of explaining it, demonstrating it, and supporting it in the field. At Sennheiser, this role is embodied by experts like Volker Schmitt encyclopedic, energetic, and unstoppable and Charly Fourcade, equally formidable and remarkably approachable.

Both are key figures behind the deserved success of Spectera, Sennheiser’s next-generation wideband digital wireless platform. At Neumann, the human dimension is personified by Martin Schneider, whom we met in his Berlin lab. For 33 years, he has been responsible for the development of Neumann microphones.

His depth of knowledge in microphone physics and electronics is immense, yet his manner is refreshingly direct and accessible. A visit to his lab includes a modest anechoic chamber, a rotating rig for polar-pattern measurements, a calibrated coaxial loudspeaker, and a lineup of power supplies representing Neumann’s entire microphone range.

One particularly revealing demonstration involves a heavy concrete tube roughly ten centimeters in diameter, positioned in front of the measurement bench. A microphone is placed inside, sealed, and then progressively amplified so its self-noise can be measured.

At extreme gain levels, even footsteps in the lab or traffic passing on Leipziger Strasse outside register clearly on the voltmeter. Martin explains that, in some cases, the tube must be moved into the anechoic chamber to validate certain measurements.

“Every measurement has limits,” he notes. “To truly measure a microphone’s self ‘noise’ electronic noise as well as the noise generated by air molecules striking the diaphragm you would need absolute zero and a vacuum. After measuring, we also listen to every microphone’s self-noise to make sure it’s clean: a very low-level thermal noise with no tonal artifacts.”

Discussions naturally turned to vintage microphones: U47s, U67s, and other iconic designs. How can one know how these microphones originally sounded and how can that sound be recreated today using different components?

Martin’s answer was immediate: “At Neumann, we keep original units in perfect working condition, with very low hours. That allows us to produce replicas that sound extremely close to what a customer would have heard when buying, for example, a U67 in the early 1960s.”

The same philosophy applies to restoration. Neumann commits to returning a faulty microphone to full original specifications. Even if aging had altered its sound before failure, the restored unit will recover its original performance, tonal character, and measured response. Capsules and diaphragms are manufactured and assembled exactly as they were at the time of original production.

As Martin adds with a smile: “Unused vintage tubes still exist—and if anyone can find small quantities of them, it’s us.”

I could easily have spent a week with Martin and written a book. Apologies are in order for monopolizing his time long enough to delay the last group of journalists waiting outside the lab but it’s not every day someone pierces a capsule diaphragm with a pencil to demonstrate its fragility and show what lies behind it. I’ve rarely opened my eyes so wide. He did, however, reassure me afterward that the capsule was already non-functional.

Between two waves of journalists, I managed to slip into the large studio where Daniel Sennheiser had welcomed us earlier, to reconnect with Volker Schmitt. I unapologetically hijacked his break to spend some quiet time listening to the handheld transmitter mic that will complete the Spectera range.

The microphone was still a prototype, visually unfinished, but fully operational. Volker handed me a Spectera SEK pack and a familiar HD 25 headset. I walked freely around the empty room talking, whispering, shouting, exaggerating sibilants and plosives, isolating myself to hunt for background noise (still looking for it).

The conclusion was immediate: this goes far beyond conventional narrowband wireless. At no point did I hear compression artifacts, HF roll-off, or any sense of bandwidth limitation. The digital transmitter/receiver pair simply disappeared sonically.

Switching to stereo music confirmed it. This is a clear break from the “FM wireless + compander + limiter” aesthetic and arguably the end of the need for enhancement processors just to make wireless sound acceptable. The sound is neutral, transparent, and true to the source.

When I asked whether we were running the most bandwidth-hungry, lowest-latency codecs available, Volker’s smile gave the answer away:

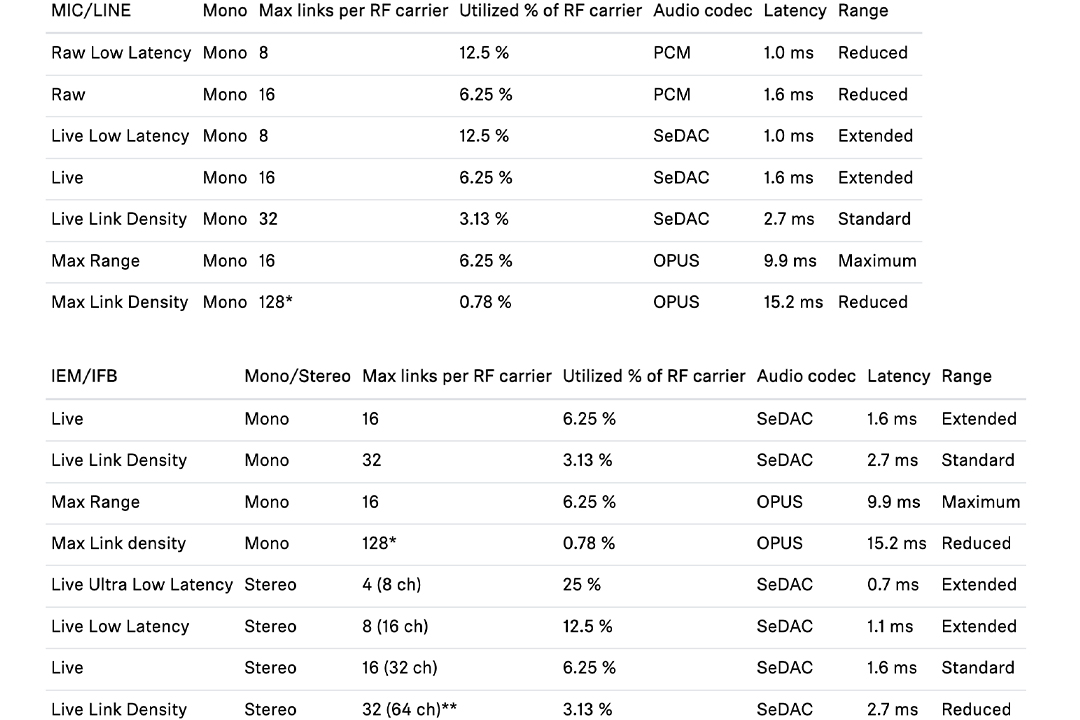

“No. This is the standard configuration on both the mic and the SEK pack, using the SeDAC codec. Total latency is 3.2 ms for 8 microphone links and 8 stereo IEM links, all running simultaneously from and to a single Base Station.”

Alternative modes include:

– Live Low Latency: ~1 ms (4 mics + 4 packs)

– Ultra Low Latency: 0.7 ms for 2 IEM links, still with 4 microphones

Listening again at the default 3.2 ms setting, the quality, dynamic range, and silence are such that most performers will simply forget latency altogether. This is genuinely wired-level performance without the wire, combined with exceptional system flexibility.

Chart showing carrier usage as a percentage of available capacity (100% maximum per Base Station). Microphone transmission at the top, in-ear reception at the bottom both add up. Flexibility is the key.

Chart showing carrier usage as a percentage of available capacity (100% maximum per Base Station). Microphone transmission at the top, in-ear reception at the bottom both add up. Flexibility is the key.

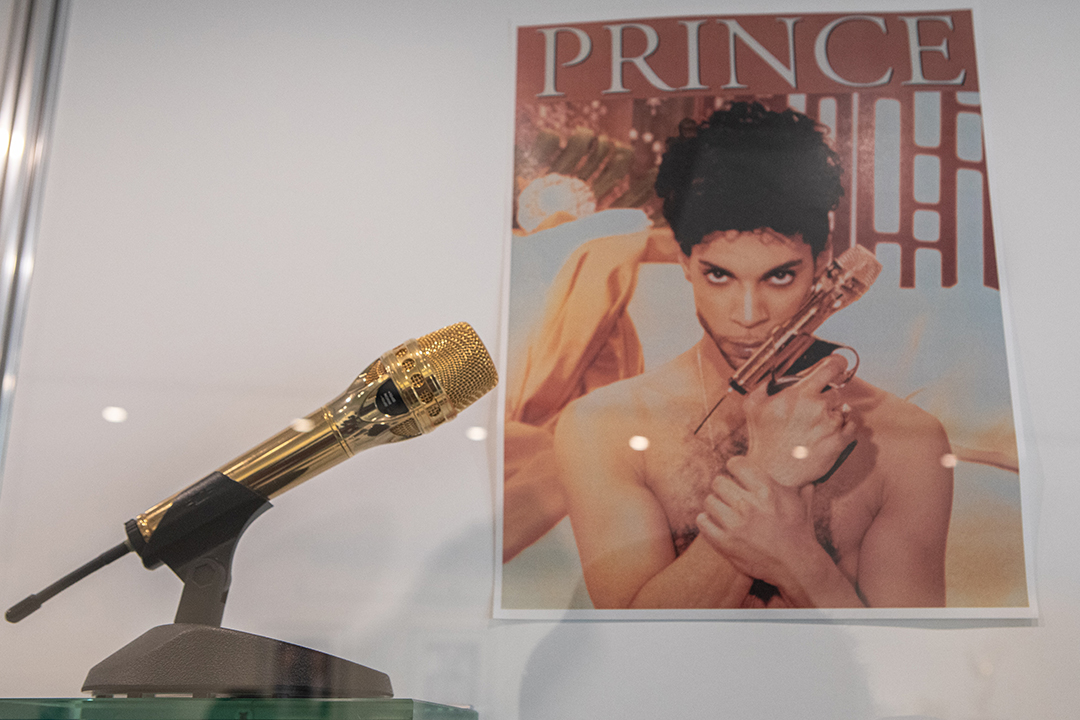

A visit to headquarters also means glass cabinets filled with objects some merely vintage, others truly iconic—at both Sennheiser and Neumann. In a few images, we’re reminded of just how much of what Germany has produced in audio technology has been innovative, faithful to the source, and timeless.

Plus d’information sur le groupe Sennheiser et sur le site Neumann

Before rolling the slideshow, a final thank-you goes to Ann Vermont, Country Manager France, Maik Robbe, Global Communications Manager, and all the teams in Wedemark and Berlin. As the clown Terracotta so aptly puts it : “You really did a tremendous job.”

Diaporama

.

The famous farmhouse where it all began—inevitably more picturesque today than it was at the time.

The famous farmhouse where it all began—inevitably more picturesque today than it was at the time.

.